A history in harmony with the passage of time

I

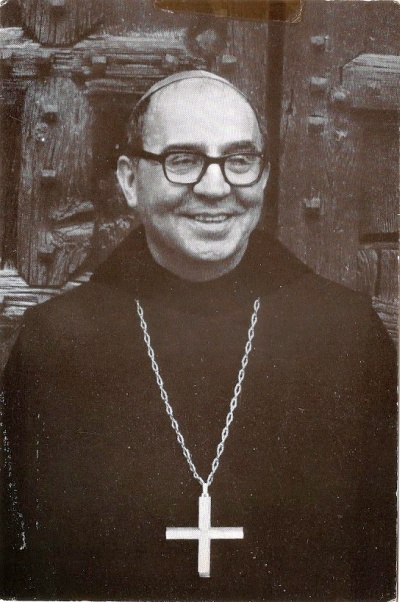

CIEMEN was brought to life in the cosmopolitan city of Milan in 1974 after several years of incubation in Barcelona and Cuixà. The founding place was just a few kilometres from where the abbot Aureli M. Escarré spent his time in exile until his death (1965-1968). The founder of the organisation, Aureli Argemí, had been his secretary at the time. Hence he incorporated the name Escarré into CIEMEN, an institution which was conceived, from the beginning, to follow in the footsteps of Escarré and the same issues that he pursued, especially those which were related to the lack of awareness among the public of Italy, and many other countries, regarding the existence of nations such as Catalonia. Ecarré reminded those who he spoke to of the words of the Spanish poet Antonio Machado when he highlighted the evil which ignorance leads to: “Spain despises everything it ignores”.

Thus, from the beginning, CIEMEN was characterised by the role it had taken up of revealing silenced truths in schools and through the media, when not being impeded by an antagonistic establishment, as was the case in Italy and many other countries, and especially in Catalonia where it was subject to the censors of the Francoist dictatorship. In order to take a stand against this situation, CIEMEN as an institution, time and time again, took on the responsibility of serving pedagogical aims. Its first public exposure was the publication of the magazine Minoranze, aimed at informing and alerting people about the existence of peoples who were being silenced and persecuted for the fact of being different. At the same time CIEMEN looked for collaborative partners who were sympathetic to their objectives. The socialist mayor of Milan, Aldo Aniasi, offered a space to the institution which he considered deserving as it was an initiative born of a democratic necessity, aiming to further democracy. He admired the slogan CIEMEN was using at the time: “diverse and equal”.

One of the first people to join CIEMEN was the Florentine essayist Sergio Salvi, who, not long before, in 1973, had achieved recognition with the publication of his work Le Nazioni proibite. His approach, besides giving information about some of the stateless nations in Europe, was to demonstrate that Europe could only fully come together, in peace and justice, if it accepted all nations which at that point had been marginalised. The book spoke out for millions of people who were defending the rights of their respective nations, who could not speak out for themselves because if they did, would be persecuted.

II

The seeds of CIEMEN were scattered across the Italian state and further afield, one of these seeds sprouted into a plant, a new headquarters, at the Abbey of Sant Miquel de Cuixà – an old monastery, recovered in 1965 by a group of monks from Montserrat, and located in the centre of Northern Catalonia, inside the state of France. This group were disciples of Escarré, their one time abbot, who had also had to go into exile with him. CIEMEN was able to take root and blossom in a place which had developed into a meeting place for people who crossed the state borders in order to find a free space, where they could compare ideas, projects and worries without the fear of seemingly arbitrary constraints. The monks of Cuixà saw the initiative of CIEMEN as an extension of the positions of Escarré and considered the organisation to be putting into practice the recent cyclical “Peace on Earth” by Pope John XXIII in which he talks about the need to read the signs of the times; one of which, without a doubt, had arisen from demands in favour of the rights of peoples.

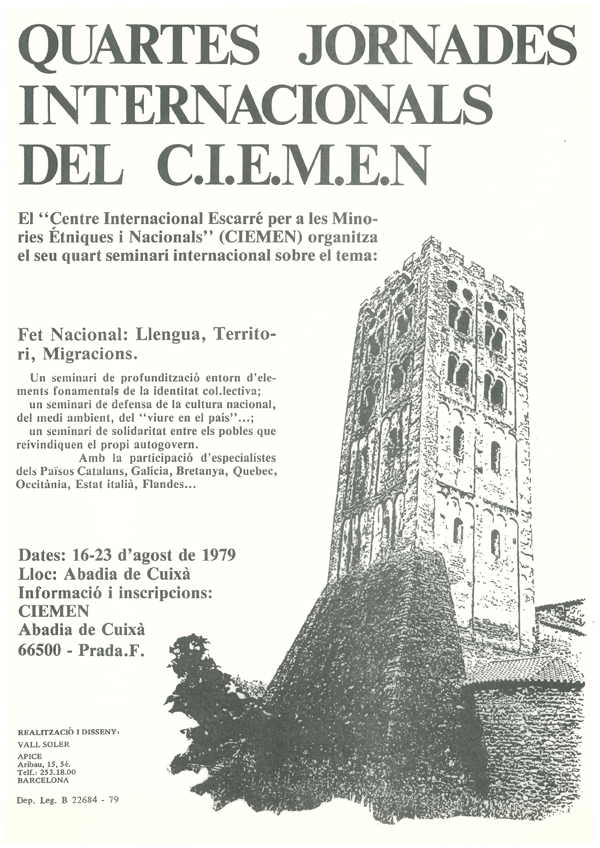

A series of initiatives came out of the new headquarters of CIEMEN, bringing together activists from stateless nations. The most important of these were the annual “CIEMEN International Conferences” which would bring together representatives from the major stateless nations of Europe. During the information sharing and discussion sessions of the conference, all types of disquieting topics were brought up, from languages and discriminated cultures to the way of preparing the structuring of the economy and the institutions which the emancipated nations would have to have, especially in a world which was becoming more and more globalised. The most important conferences began to be collected in a series of books, organised by CIEMEN, called Nationalia – a Latin word used to bind together the different languages in which the various contributions were published in.

III

After the death of Franco (1975), as stateless peoples of Spain, administered by the central government of Madrid, were mobilising to recover their rights, CIEMEN was establishing a new headquarters in Barcelona, capital of Catalonia. From the start, the institution concentrated its efforts on spreading its ideals, while the political parties were fighting to position themselves in the incipient democracy. Faced with the danger of national rights remaining minimal concern or put on hold by those politicians who were making themselves heard the most, CIEMEN deemed it the right time to set up the Peoples’ International Tribunal of Justice which would remain vigilant regarding national rights, complementing the project which CIEMEN itself had presented in the first CIEMEN International Conference (1976).

On the other hand, seeing how the historic demands to strengthen the links between the Catalan countries was being played down in the programmes of the different political parties most implicated in the issue, CIEMEN published a special edition of its magazine, titled I Paesi Catalani, in which the defence of the Catalan countries remained closely connected to the national question of each constituent part.

CIEMEN manifested its dismay towards the passing of the Spanish Constitution (1978) in which the national rights of Catalans, Basques and Galicians were not recognised in any way. The institution positioned itself for the no vote for the referendum to ratify this Magna Carta. Its “no” would be repeated with consistent arguments confirming how the spirit of Francoism was being prolonged in the supposed process of democratisation; a spirit which had infiltrated the instructions that the politicians had to accept the way of reform, of transition, rather than a break with the past and an opening up, without limits, to the concepts of democracy.

Once again, CIEMEN condemned the positions in favour of transition which were infiltrating the legislation being written up by the Parliament of Madrid, based on a consistently restrictive interpretation of the same Constitution which formally respected the above-mentioned nationalities. The shortage of perspectives was made clear, for example, in the text of the Statute of Catalan Autonomy and in the other statutes for the Basque and Galician “nationalities” – statutes which had more to do with the decentralisation of the Spanish state than with a substantial response to the claims of the stateless nations.

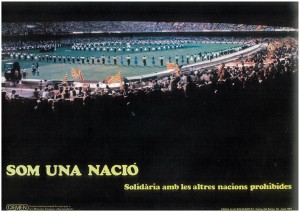

The general disillusionment with the reactionary process of Spanish politics reached its nadir with the attempted coup d’etat on 23 February 1981. One of the effects of this event was an increase of already shamelessly regressive and recentralising policies, with the corresponding reduction of autonomous powers and the condemnation of opposition. In this context, CIEMEN proposed relaunching the previously mentioned Tribunal for defending national rights. But while its members discussed how to carry this out, voices arose from Catalan civil society demanding a popular mobilisation to stand up against the ever more evident disdain and persecution on behalf of the central government towards the Catalan language and culture which they had been winning back. CIEMEN took part in its promulgation and, along with other institutions, promptly became one of the leading associations in the creation of the popular movement of national affirmation. On 18 March 1981 a period of social mobilisation began under the banner of the Call for Solidarity in Defence of the Catalan Language, Culture and Nation, which continued for over ten years, with a large impact on the process of responding to anti-Catalan policies and on the dynamics being faced in promoting a national reconstruction.

In order to carry out the objectives of the Call, CIEMEN contributed to the formation of an assembly of institutions which worked on serving the different sections which the Call had been split into. CIEMEN put its efforts, above all, into the running of the Secretariat and the sections of language promotion, international relations and cooperation. During the early stages, the headquarters of the Call were based at CIEMEN.

The fruits of their labour for promoting the language became apparent through various actions taken to encourage the social use of the language and to defend its linguistic rights. What followed was the catalanisation of various private and public companies, from large commercial stores to Barcelona airport. And, as far as language rights are concerned, the work which had been carried out came to a head in 1996 with the Universal Declaration of Language Rights, a document with international repercussions, promoted and edited by a group from CIEMEN, the Catalan PEN Club and experts from around the world. The document was passed in the framework of the Global Conference on Language Rights, organised in Barcelona by CIEMEN and the PEN Club in June 1996.

As for collaboration with the international department, CIEMEN’s activities focused on promoting popular demonstrations at the seat of the European Parliament in Strasbourg in 1985 where they presented a document which had been written up by CIEMEN itself and was received by the presidency of the Parliament. The document, put together in the form of a petition, called for the entry of the Catalan nation into the then European Community, as a distinct nation. The petition was carried out months before the entry of the Spanish state as a fully-fledged member into those European institutions (1986). Another initiative, which was coordinated by CIEMEN, along with other organisations, was the delivery to the European Parliament of 100,000 signatures demanding the recognition of Catalan as an official language (1991). A third noteworthy initiative, in which CIEMEN was a pioneer, was the communcal gathering, co-organised with representatives of various stateless nations, in front of the headquarters of the UN in Geneva in 1996. Here they handed over a letter addressed to the Secretary General in which they urged him to act to have a ruling passed in the General Assembly which would prioritise the exercising of the right to self-determination of currently marginalised nations, as a contribution to the peace and understanding between peoples. Finally, in the framework of relations with international institutions, an organised trip to Paris was a particular highlight – a group of Catalans filled a train, called the Train of Nations (1987), in order to hand over a text, written by CIEMEN, to the headquarters of UNESCO, in which it requested the acceptance of the Catalan nation as a member of this global institution, dedicated to serving the cultures of the different peoples of the planet.

Within the department of cooperation, CIEMEN promoted various acts of collaberation with especially disadvantaged peoples. There was a particularly high participation among Catalan society in the campaign to help the people of Ethiopia and Eritrea (1986). At the same time, CIEMEN was one of the founders of the Fons Català de Cooperació al Desenvolupament (Catalan Development Cooperation Fund), which, over time, came under the coordination of the councils of Catalonia.

Aside from its links to the Call, CIEMEN, as an independent organisation, has participated in and promoted many other initiatives on an international scale. On a linguistic level, CIEMEN, first assuming the presidency and then becoming a member of the board of governors, joined the European Bureau for Lesser-Used Languages (EBLUL), an association with representatives from the minority languages of the European Union which acted as a spokesperson in the European Parliament and was financed, primarily, by the European Commission. At the same time, and still with the initial support of the Call, CIEMEN began to set up the Conference of Stateless Nations of Europe (CONSEU), an intersectional platform for reflection and debate, to bring together different groups with the aim of channelling their struggles in favour of the rights of peoples within European society and throughout the world.

In accordance with this initiative, but also expanding on it, CIEMEN joined the network of organisations around our planet which fight for social and political emancipation, for another possible world, which come together at the Global Social Forum. CIEMEN has been active in the network, reaching a high point with the introduction of the national question into the agenda as one of the most important issues to deal with. The fruit of this participation was the formation of the Global Network for the Collective Rights of Peoples, with its office in Brussels, made up of civil organisations from around the world, with CIEMEN taking the role of Secretariat.